Primaquine is the essential co-drug with chloroquine in treating all cases of malaria. It is highly effective against the gametocytes of all plasmodia and thereby prevents spread of the disease to the mosquito from the patient. It is also effective against the dormant tissue forms of P. vivax and P. ovale malaria, and thereby offers radical cure and prevents relapses. It has insignificant activity against the asexual blood forms of the parasite and therefore it is always used in conjunction with a blood schizonticide and never as a single agent.

Mechanism of action is not well understood. It may be acting by generating reactive oxygen species or by interfering with the electron transport in the parasite.

Absorption, fate and excretion: It is well absorbed after oral administration and rapidly metabolised. Its elimination half-life is about 6 hours. The metabolites of primaquine have oxidative properties and can cause hemolysis in susceptible patients.

Adverse effects: In therapeutic doses, primaquine is well tolerated. At larger doses, it may cause occasional epigastric distress and abdominal cramps. This can be minimised by taking the drug with a meal. Mild anemia, cyanosis and methemoglobinemia may also occur. Severe methemoglobinemia can occur rarely in patients with deficiency of NADH methemoglobin reductase. Granulocytopenia and agranulocytosis are rare complications.

Use in Malaria: Primaquine has been the only 8-amino quinoline drug available since 1952 for the radical cure of P. vivax (and P. ovale) malaria by its action on the dormant hypnozoites. It also enhances the efficacy of chloroquine, particularly in the setting of resistance to chloroquine.[1-4]

Patients with deficiency of Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase will develop hemolytic anemia on taking usual doses of primaquine. This problem is restricted to certain sections of the population. It may not be practical to test each and every patient for G 6 PD deficiency before administering primaquine. If a patient is known to be severely G6PD deficient, then primaquine should not be given. For the majority of patients with mild variants of the deficiency, primaquine should be given in a dose of 0.75 mg base/kg bw once a week for 8 weeks. If significant haemolysis occurs on treatment, then primaquine should be stopped.[Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. World Health Organization. Geneva, 2006. pp 62-68. Available at http://apps.who.int/malaria/docs/TreatmentGuidelines2006.pdf]

Primaquine should not be used in patients who have severe systemic illness that is likely to cause leukopenia (severe rheumatoid arthritis, SLE etc.). It should not be used with other drugs likely to cause bone marrow depression.

Patients with G6PD deficiency may develop hemolysis with quinine. (Mosby’s Drug Consult, 2002 p.III-2387-2388). A study in healthy subjects indicates that concurrent administration of primaquine can increase blood concentrations of mefloquine and may increase the adverse effects due to mefloquine. (Martindale 31st Edition, 1996; 468-469). Therefore, simultaneous use of quinine or mefloquine is contra indicated.

Availability: Primaquine is available as tablets containing 2.5, 7.5 and 15 mg of the salt.

| Dose of Primaquine according to NVBDCP, India |

||

| Age in years | P. vivax/mixed infection (once daily for 14 days) | P. falciparum infection (Single Dose) |

| 0-1 | Nil | Nil |

| 1-5 | 2.5 mg | 7.5 mg |

| 5-9 | 5 mg | 15 mg |

| 9-14 | 10 mg | 30 mg |

| >14 | 15 mg | 45 mg |

For effective radical cure, primaquine must be used in full dose as per body weight for 14 days. Although most recommendations, including the NVBDCP-India, suggest a dose of 0.25mg/kg/day, at an average of 15mg/day, for 14 days, it may not be effective in some, particulalry those with a much higher body weight. As shown in the Table below, CDC and WHO do recommend a higher dose.

| Agency | Dose of Primaquine |

| CDC | 0.5 mg/kg/d for 14 days (max. of 30 mg/d) |

| WHO | 0.25 mg/kg/d for 14 days except in Oceania and Southeast Asia; 0.25 to 0.75 mg/kg/d X 14 days are effective |

| NVBDCP | 0.25 mg/kg/d for 14 days |

Therefore, if a patient develops a relapse after full dose of radical therapy (15 mg/d for 14 days regimen), higher dose according to body weight, of 22.5 mg or 30 mg per kg body weight for 14 days may be needed.

Studies have reported primaquine treatment compliance to be as low as 30% and that >80% of clinical attacks of P. vivax in an endemic area may be derived from hypnozoites, owing to improper of incomplete radical treatment. [5,6] Efficacy of primaquine depends on total dose administered and is reduced 3-4 fold if ≥ 3 of the 14 doses are missed [see figure below].[7,8]

| The Primaquine Questions – Confusions in Primaquine Use in Malaria | |

| To use or not? | Often primaquine is not prescribed for falciparum malaria because it is not needed for attaining a cure of the infection. But it is required to prevent the spread of falciparum infection because unlike in case of P. vivax malaria, chloroquine does not sterilize the gametocytes of falciparum species. Therefore, if primaquine is not used in falciparum malaria, there will be a selective spread of P. falciparum malaria, which may be even resistant to drugs. Therefore, do not forget to use primaquine in P. falciparum malaria- prevent the spread of P. falciparum, prevent the spread of drug resistant strains! Primaquine is hence a must for both P.vivax and P.falciparum infections. |

| What is the dose? | 0.25mg/kg/day (once a day) for 14 days in P. vivax (or higher, see above); 0.75 mg/kg as single dose in P. falciparum. |

| What is the alternative to primaquine? | At present, Primaquine is the only drug available for tissue schizonticidal activity in P. vivax malaria and gametocytocidal activity in P. falciparum infection. Therefore, it must be used in both these infections. Therefore, at present there are no alternatives to primaquine. Newer anti malarials like mefloquine or artemisinin derivatives are NOT substitutes for primaquine! |

| Is there primaquine resistance? | Although resistance to primaquine has been reported from SE Asia and Africa, it is rare. Such cases are managed with a higher dose of primaquine. |

| Primaquine or ‘parda’? (Mosquito nets) | In some hospitals, patients with malaria are made to lie inside mosquito nets, with the idea of preventing the spread of the infection to the ‘hospital mosquitoes’ and hence to other patients. Often these patients are not administered primaquine. Remember, mosquito nets may not prevent the spread of falciparum malaria, but Primaquine WILL. |

Tafenoquine, another 8 aminoquinoline for the radical cure, has been approved by the US FDA in July 2018.[8] It has a half life of 15 days and therefore is suggested at a single dose of 300mg for adults. It is not recommended for pregannt and lactating women andfor those with G6PD levels lesser than 70% of normal.[8.9]

Glucose 6 Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency

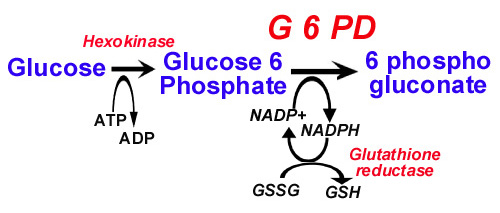

Glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase is an enzyme in the Hexose Monophosphate shunt. This shunt generates reduced glutathione that protects sulfhydryl groups of hemoglobin and the red cell membrane from oxidation by the oxygen radicals. Defects in the shunt leads to inadequate protection against oxidation, resulting in oxidation of sulfhydryl groups and precipitation of hemoglobin as Heinz bodies and in lysis of the red cell membrane.

Deficiency of Glucose 6 phosphate dehydrogenase is the most common among the congenital shunt defects, affecting more than 200 million people in the world. There is considerable genetic heterogeneity among affected individuals with over 400 variants of the enzyme identified. Therefore the severity of the problem can vary from hemolysis even in the absence of oxidative stress to hemolysis only on exposure to mild to marked oxidant stress.

The normal G6PD is called as Type B. Type A- has two base substitutions and is seen in people from central Africa. A second variant is seen among the people of the Mediterranian and is more severe than Type A-. The third variant that is relatively more common but less severe is seen in southern China.

The defect is known to provide partial protection against malaria, by providing defective environment in the affected red cells.

The G6PD gene is located on the X chromosome. Thus the deficiency state is an sex-linked trait seen only in hemizygote males. Most female carriers are asymptomatic.

Hemolytic episodes may be triggered by viral or bacterial infections and by drugs or toxins that have an oxidating potential. Antimalarials like primaquine, pamaquine, dapsone, sulfonamides like sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, vitamin K, doxorubicin, methylene blue, nalidixic acid, furazolidone etc. and naphthalene balls can cause hemolysis in defective individuals.

The hemolytic crisis may manifest within hours of exposure to oxidant stress. In severe cases, hemoglobinuria and peripheral circulatory collapse can occur. Since only older red cells are affected most, the problem is usually self-limiting. There will be a rapid drop in hematocrit, rise in plasma hemoglobin and unconjugated bilirubin. Heinz bodies can be seen on crystal violet staining. These are removed in the spleen in a day or two and ‘bite cells’, with loss of a portion of the periphery of the red cell, may be seen.

The diagnosis can be confirmed by G6PD assay. The test may be negative during a hemolytic crisis when the older and defective RBCs are replaced by younger cells. In such cases, the test has to be repeated. Now a point-of-care RDT that detects G6PD deficiency is available, however, it has a cut-off limit at <30% of normal activity and therefore will detect only such cases. It is not yet available for routine use.[10]

No specific treatment is needed since the condition is usually self limiting. Rarely blood transfusions are indicated. Adequate urine output should be ensured.

If a patient is known to be severely G6PD deficient, then primaquine should not be given. For the majority of patients with mild variants of the deficiency, primaquine should be given in a dose of 0.75 mg base/kg bw once a week for 8 weeks. If significant haemolysis occurs on treatment, then primaquine should be stopped.[Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. World Health Organization. Geneva, 2006. pp 62-68. Available at http://apps.who.int/malaria/docs/TreatmentGuidelines2006.pdf]

References:

- Cotter C et al. The changing epidemiology of malaria elimination: new strategies for new challenges. The lancet. September 2013;382(9895):900–911, 7

- Mueller I et al. Key gaps in the knowledge of Plasmodium vivax, a neglected human malaria parasite. Lancet Infect Dis 2009;9:555–66.

- John GK et al. Primaquine radical cure of Plasmodium vivax: a critical review of the literature. Malar J. 2012;11:280.

- Fernando D, Rodrigo C, Rajapakse S. Primaquine in vivax malaria: an update and review on management issues. Malaria Journal. 2011;10:351. At http://www.malariajournal.com/content/10/1/351

- Khantikul N et al. Adherence to Antimalarial Drug Therapy among Vivax Malaria Patients in Northern Thailand. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27(1): 4–13. At https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2761802/

- Abreha T et al. Comparison of artemether-lumefantrine and chloroquine with and without primaquine for the treatment of Plasmodium vivax infection in Ethiopia: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2017;14(5): e1002299. At https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002299

- Takeuchi R et al. Directly-observed therapy (DOT) for the radical 14-day primaquine treatment of Plasmodium vivax malaria on the Thai-Myanmar border. Malaria Journal. 2010;9:308. At https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2875-9-308

- FDA. Single-Dose Tafenoquine 300 mg for Radical Cure of Plasmodium vivax Malaria. GlaxoSmithKline Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting, July 12, 2018. At https://www.fda.gov/downloads/advisorycommittees/committeesmeetingmaterials/drugs/anti-infectivedrugsadvisorycommittee/ucm614040.pdf

- Llanos-Cuentas A et al. Tafenoquine plus chloroquine for the treatment and relapse prevention of Plasmodium vivax malaria (DETECTIVE): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, phase 2b dose-selection study. The Lancet. March 2014; 383(9922):1049–1058. At http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736%2813%2962568-4.pdf

- Satyagraha AW et al. Assessment of Point-of-Care Diagnostics for G6PD Deficiency in Malaria Endemic Rural Eastern Indonesia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 Feb; 10(2): e0004457

©malariasite.com ©BS Kakkilaya | Last Updated: Oct 15, 2018